Author: Liz Busch

Do you feel that your organization may not be strategically procuring the goods, services and construction it needs? You’re not alone! Some organizations manage procurement reactively, where each acquisition is a stand-alone procurement once a need is identified which can ultimately result in multiple separate procurements for similar commodities. Overall, this approach can cost more, both in staff time and contractor payments.

If this sounds familiar, what can help move an organization from reactive to a strategic procurement approach? Read on for 10 steps to get you there!

1. Executive Support

Support from executives is required to overcome constraints and objections, as those with authority can clear the path. However, this support may be in principle only at first, as executives will want fulsome information on costs and benefits before fully supporting the change.

2. Business Intelligence

What is the organization buying? This can be challenging to determine, as not all public sector organizations have effective systems to track and report this information. Look for trends, where the organization is buying similar commodities through independent solicitations or direct awards and entering discrete contracts and purchase orders for each. This analysis will identify commodities that could benefit from standing arrangements, such as prequalification lists, standing offers and as if and when contracts. An internal communications plan will also be needed to inform buyers of the existing arrangements they should use.

Also consider any long-term contracts that may not have been competed for some time (e.g. legacy computer system support). If these contracts are renewed year-after-year without considering alternatives, the time is ripe to investigate the benefits of change.

3. Identify Needs

Business intelligence is based on historical purchases and therefore may not capture all existing and emerging needs. Discussions with the organization’s work units on what has recently changed or might soon could uncover new commodities that could benefit from standing arrangements, or historical acquisitions that are no longer needed.

4. Market Research

Investigate the markets for the commodities identified as potentially benefiting from standing arrangements. How many vendors supply each commodity? What’s happening industry-wide that may impact the supply chain or pricing? Are there buying groups that you could join who have already done this research and have established supply arrangements? Investigate more than just the local market as national and international vendors may meet the need best.

5. Procurement Analysis

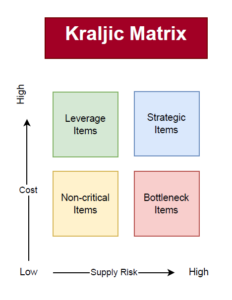

Analyze and group the identified commodities and markets. The Kraljic Matrix is one tool that can help with this, noting that it has been adapted somewhat for the public sector.

- Non-critical items are generally inexpensive and standardized, and can be purchased from many vendors (e.g. office supplies, janitorial services). Even though each purchase is small, over time a lot may be purchased and considerable administrative effort may be needed acquiring them. These commodities can benefit from standing arrangements with easy ordering processes.

- Leverage items are costly to buy but relatively standardized, and are offered by many vendors (e.g. fleet vehicles, construction services). Given the competition that exists, bargains can be had. Consider arrangements that allow for switching vendors if a better deal can be had, rather than locking into long-term contracts.

- Bottleneck items are not costly, but few vendors sell them, or the supply chain is unreliable (e.g. an electronic component that is only sold by one manufacturer, anything impacted by the current computer chip shortage, laboratory services). These commodities can benefit from long-term contracts and investigating alternative approaches or substitute products.

- Strategic items are both costly and can only be purchased by one or few vendors (e.g. speciality scientific equipment, expert negotiators for high-dollar complicated contracts). Collaboration and strategic partnerships can work well for these commodities, where a long-term relationship is established with one or two vendors.

6. Organizational Objectives

What are the organization’s procurement objectives? Almost all public sector entities want to maximize budgets and receive value for money, but many are now adding social and environmental goals. Examples include the City of Vancouver’s living wage policy and the Government of Canada’s Policy on Green Procurement.

7. Organizational Reputation

How does the vendor community view the organization? Is it seen as a client-of-choice, or do vendors think it’s difficult to work with or the solicitation processes are onerous? An organization’s reputation will impact the strategy, as this determines how willing vendors are to work with and respond to its opportunities. Consider outreach and networking opportunities where vendors provide input into what works well and what’s difficult for them, and address this feedback in your strategy.

8. Constraints

All public sector entities have constraints, usually related to staffing and budgets, but others may also exist (e.g. technology requirements, legislation and regulations, dependencies with other government units, the organization’s reputation, etc.). A fulsome understanding of these constraints is needed as they impact what is possible for the strategy. Also consider how these constraints can be eliminated or reduced, such as hiring contractors to augment staff, and creating working groups that include everyone impacted.

9. Strategic Plan

Develop a report that summarizes the research and analysis done and provides options and recommendations. This report can be used to get final decisions on what to include in the strategy, and to solidify executive support.

Based on what is approved, write a Strategic Plan using the acronym SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, results-oriented, and timebound). Include who is responsible to do what, a monitoring plan to effectively track progress, and a clear change management process to adjust as needed. Widely publish the approved Strategic Plan and create working groups to implement it.

10. Ongoing Changes

An organization’s procurement needs are not going to remain static. Create a process of regular updates to the Strategic Plan, where progress can be documented and celebrated, and changes can be made as needed. This requires ongoing research and analysis on the organization’s spending, the applicable industries, and any changes to reputation, all of which can impact what changes.

We invite you to checkout our training and service offerings pertaining to public sector procurement.

- Training for me: https://theprocurementschool.com/public-sector-procurement-program-pspp-training-for-me/

- Training for my team: https://theprocurementschool.com/webinars-training-for-my-team/

- Consulting services: https://theprocurementschool.com/services/consulting/

- Custom training services: https://theprocurementschool.com/services/custom-training/

Author: Liz Busch

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the Subject Matter Experts and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Procurement School.